It is with great sadness that we learn of the death of Andrée Geulen. During the occupation, Andrée worked as a courier for the Jewish Defense Committee – Comité de Défense des Juifs, the largest hiding network in Belgium. Together with her Jewish and non-Jewish colleagues of the children’s department, Andrée saved more than 2,000 Jewish children from deportation. After the war, this grande dame dedicated herself to justice, fought against inequality, racism and anti-Semitism. With her, the last employee of the Jewish Defense Committee has passed away. Kazerne Dossin wishes her daughters, her family and her nearest and dearest much strength.

Andrée Geulen was born on 6 September 1921 in Brussels as the second daughter of the liberal, well-to-do family of Gaston and Josephine Geulen. As a twelve year old Andrée went to the lyceum, where she ended up in a class that was very politically and socially engaged. The girls organised collections for the war in Spain and after the Anschluss in 1938 they collected money for Austrian refugees. Andrée was in the scouting movement. The members went to the station of Schaarbeek to distribute food to refugees coming from trains from Austria and Germany, sometimes transports with only children only. The scouts would pick up those children from the station and bring them to the boarding school Foyer des Orphelins in Molenbeek. André’s social awareness grew rapidly through these initiatives, as did her aversion to Nazism.

On 10 May 1940, the day of the German invasion, Andrée was at school. She was at boarding school at the école normale in Endennes and woke up to the bombs. The Meuse River was nearby and the bridges were being bombed. Some teachers from Brussels brought Andrée home by train. However, the bridge between the school and the railway station had already been bombed so they had to cross in a small boat between the bombs. It took a whole day to get back to Brussels. Andrée took her last secondary school exams in a Brussels school.

The summer of 1942 was a turning point for Andrée. The headmistress of her school in Endennes hired her to take care of children who were having difficulties at home in a children’s colony during the summer. One evening, a small child hugged her and confided in her that he was Jewish and his name was Charles Majerowicz. Only then did Andrée realise that there were children in hiding. From September onwards, Andrée did temporary jobs as a teacher in Brussels. One day, a child with a star entered the classroom. For Andrée, that was a stigma of discrimination: a child is a child. When more and more children stayed away from school and Andrée went to find out about their fate, she heard about the razzias and deportations.

At the beginning of 1943, Andrée taught substitute French at the Institut Gatti de Gamond, directed by Odile Ovart. She informed Andrée that twelve Jewish children were hiding in the school. At Whitsun, the Sicherheitspolizei-Sicherheitsdienst (Sipo-SD) raided the school. he Jewish children and their educator Hélène Gancarska, as well as the headmistress, her husband and daughter, were taken to the offices of the Sipo-SD in Avenue Louize. The daughter of Mr and Mrs Ovart was then released. With the exception of two of the children, the other detainees were all deported. Only Hélène Gancarska survived and was repatriated. Andrée barely escaped the razzia. It was also Odile Ovart who introduced Andrée to Ida Sterno. Ida was in charge of the placement service of the children’s section of the Jewish Defense Committee, and was looking for a courier who would pick up Jewish children from their homes to hide them. Andrée did not hesitate for a moment. She joined the Defence Committee but was not allowed to tell her parents.

Andrée would work for the Jewish Defense Committee for the rest of the war. Ida Sterno was her immediate superior. Her closest colleagues were Claire Murdoch and Paule Renard. The Jewish families that Andrée visited mainly lived in Saint-Gilles and Vorst, around the Brussels-North and Brussels-South stations. Andrée often went on foot. Nobody paid any attention to her, she looked innocent. Andrée learned the address of a Jewish family by heart and went to visit the families to convince the parents to give her their children. Andrée took small children to hiding families, the older children to children’s colonies, boarding schools, monastery schools, etc. Everything was done in the greatest secrecy. The committee members did not know each other’s real names and met regularly in new places to exchange information. Andrée had very little contact with her family in 1942-1944 to protect herself and them. She did share a flat for a while with Ida Sterno who was evicted from her rented room when the owner discovered that she was Jewish.

Andrée worked for the Jewish Defense Committee until the end of the occupation. In later interviews, she told how difficult it was to convince mothers to entrust her with their children. Had she been a mother herself, she agreed, she would never have been able to do this work. The stories in which Andrée arrived just too late, where families were arrested almost under her nose, stayed with her the most. After the war, Andrée remained in the service of its successor, the Aide aux Israélites Victimes de la Guerre. As an employee, she tried to reunite as many former hiders as possible with their families. Then she worked for the American army for a while. Andrée married Charles Herscovici in 1948 and started a family, but she remained committed to the fight against inequality. Injustice was a thorn in her eye.

Together with her colleagues from the children’s department, Andrée saved more than 2,000 Jewish children in Belgium from deportation. She maintained warm ties with these boys and girls after the war. Her phenomenal memory enabled her to recognise many of the children decades later and to tell them exactly where they were hiding during the war, partly thanks to the coded notebooks used by the Defence Committee to keep track of their trail. Many children had been too young to remember anything of their own history after the war.

In 1989, Andrée was awarded the title of Righteous Among the Nations by Yad Vashem for her rescue work, and in 1991, she participated in the first major international gathering of former children in hiding in New York. She maintained close ties with the Belgian association for children in hiding L’Enfant caché asbl. The Centre Communautaire Laïc Juif awarded her the title of Mensch of the Year in 2004, a title given to persons of great merit to the Jewish community, and in 2007 she became an honorary citizen of Israel. In 2008, she told her story in detail and that of her colleagues in the film ‘Un simple maillon‘ by Frédéric Dumont and Bernard Balteau. In September 2021 André’s 100th birthday was celebrated extensively. Canvas made the documentary ‘Mademoiselle Andrée’ in which this grande dame is honoured. In mid-March this year, barely ten weeks ago, she was recognised as an honorary citizen of Ixelles.

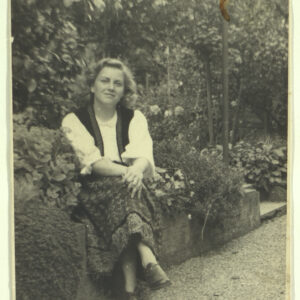

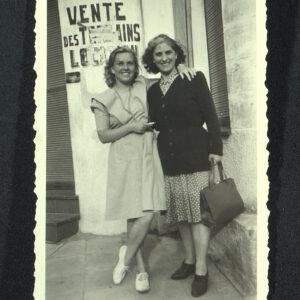

Andrée was a strong woman. She was aware of the importance of commemoration, took an active role in the fight against anti-Semitism and racism, and therefore entrusted Kazerne Dossin with, among other things, her diary in which she noted down more than 1,000 names of Jewish children from Brussels who were hidden by her and her close colleagues during the war. Only this morning Kazerne Dossin digitised one of her photo albums from the immediate post-war period, when Andrée worked for the American army. André’s story will be remembered, she and her heroic deeds will not be forgotten.

Kazerne Dossin wishes André’s daughters, her entire family and her loved ones a lot of strength in these difficult times.