What we do

Mission

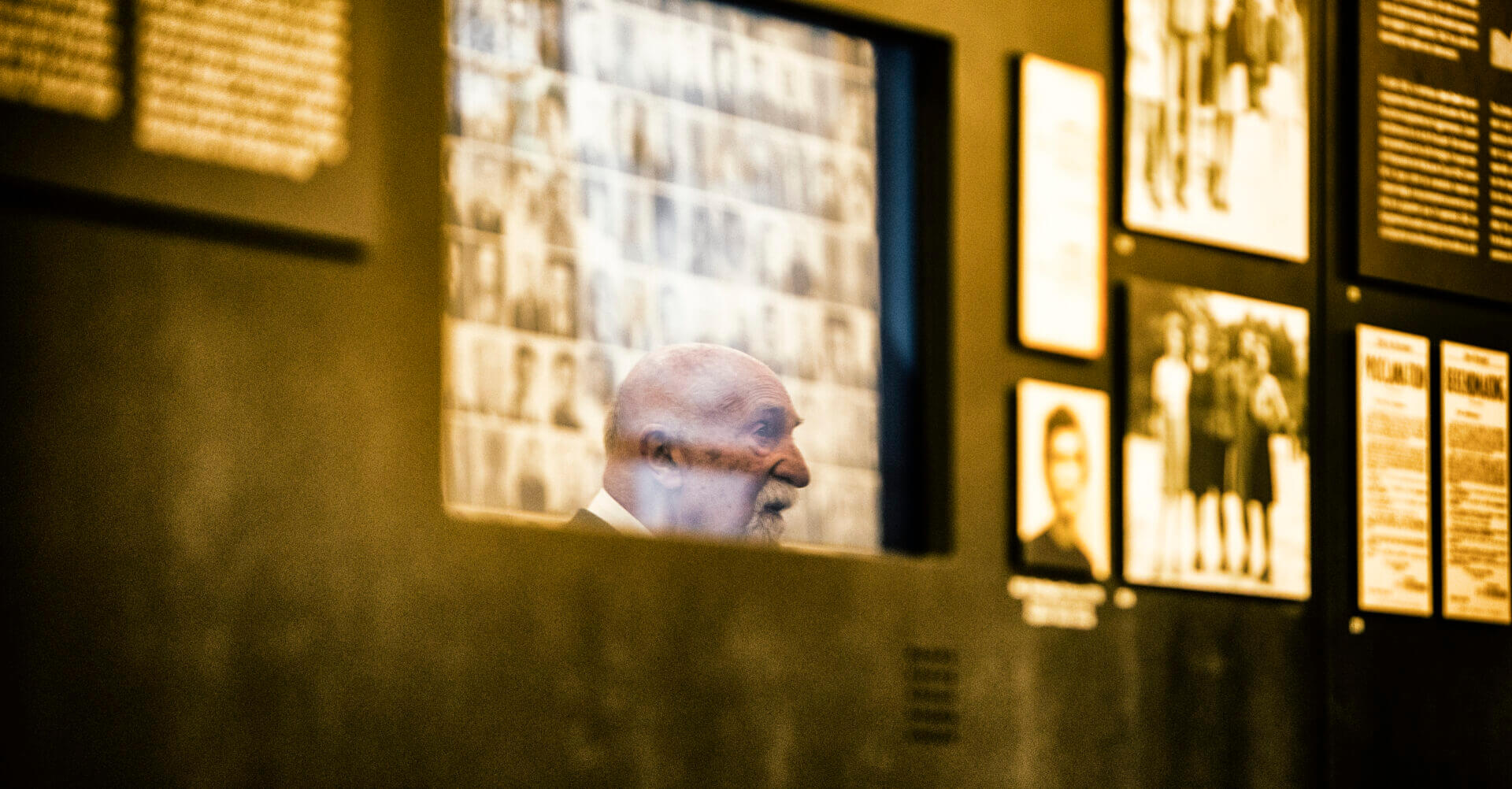

‘Kazerne Dossin draws on the historical account of the Jewish persecution and the Holocaust from a Belgian perspective as a means to reflect on contemporary phenomena of racism and the exclusion of communities, and on discrimination for reasons of origin, faith, belief, colour, sex or sexual orientation.

In addition, Kazerne Dossin seeks to analyse the issue of group violence within society as a possible stepping stone to genocide.

In this way, the museum makes a fundamental contribution to the educational and social project, in which citizenship, democratic resistance and the defence of individual basic freedoms are central.

In 2021, visitor numbers rose again after the corona crisis. Kazerne Dossin also grew as a specialised research institution and archive. Staff members took an active role in national and European cooperation projects relating to the Holocaust. They informed the media, advised stakeholders and welcomed researchers in the reading room. Kazerne Dossin also received more gifts and loans for the archive.

The significance of Kazerne Dossin was also made relevant through collaborations with various partners. By developing learning pathways with the judiciary to combat racism, by organizing training courses for prison guards and re-launching the We-They (Wij-Zij) expertise network on polarization, the institution is involving new partners and target groups in the mission.

Read the annual report 2021

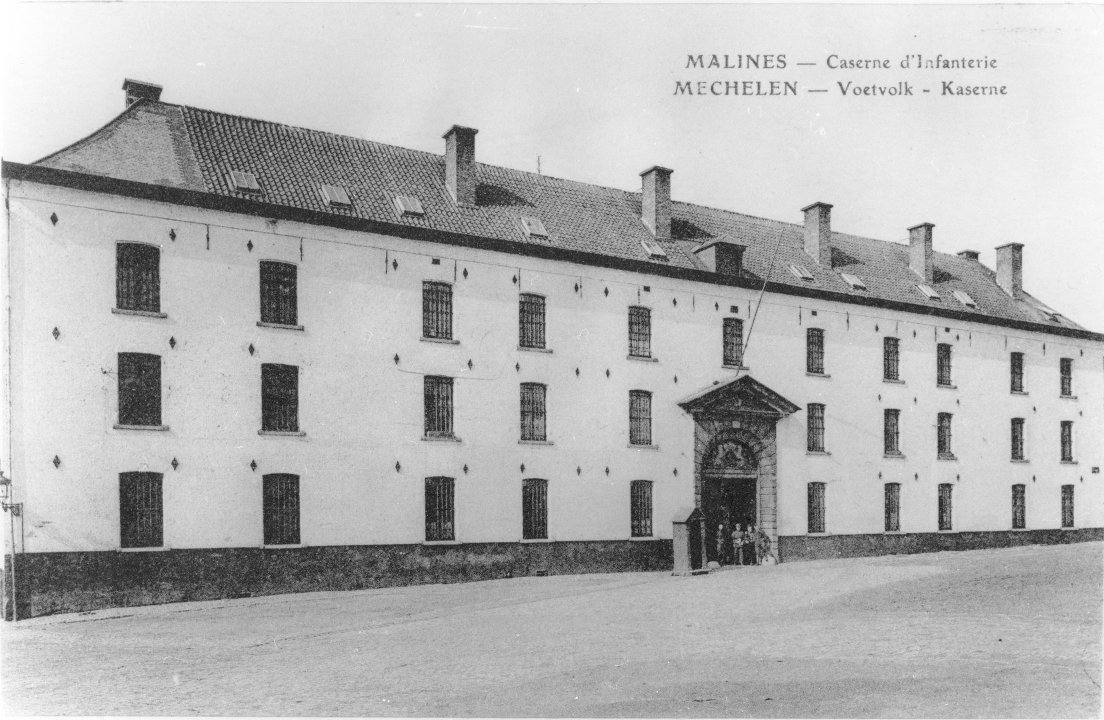

In 1756, Empress Maria Theresa of Austria commissioned the construction of the barracks to accommodate Austrian soldiers. The architects meticulously followed the orders of the Supreme Command in Vienna, which gave the building its sober and stern exterior. This reflected the Viennese classicism rather than blending with the local architecture. In 1781, the Austrian emperor visited the barracks and later the city of Mechelen sold the barracks to the state.

Between 1781 and 1940, the barracks played a pure military role, which was met in various ways. Until 1914, the building served as depot for the regiments of Grenadiers, Riflemen and Third Rifles Guards. Later it became a weapon depot and from 1918, an auxiliary depot of the 7th Line regiment. In 1936, the barrack received the name of the commander of this regiment during the First World War: Lieutenant-General Emile de Dossin de Saint Georges (1854-1936). A resident Liège (Belgium), he was honoured as war hero, because of his crucial role in the Battle of the Yser (17-31 October 1914).

The function of the barracks between May 1940 and July 1942 remains a riddle but afterwards, the building got a very sinister reallocation. Just like Vught and Westerbork in the Netherlands and Drancy in France, the barracks were designated ‘Sammellager’, a transit camp for Jews, Roma and Sinti. The central location of the barracks (between Antwerp and Brussels where most of the Jews lived), the railway next to the barracks, and the enclosed structure made this location the ideal deportation centre. Between July 1942 and September 1944, 25,490 Jews and 353 gypsies were rounded up and transported to Auschwitz-Birkenau and to a number of smaller concentration camps. Two-third of the deported persons was gassed immediately upon arrival. At the liberation of the camps, only 1,395 were still alive.

After WWII, the Dossin barracks was repossessed by the Belgian state. At the end of 1948, the Belgian army established a school in the barracks for the administration of the Army. In June 1950, a training centre of the Financial Services was added to the complex.

On 30 May 1948, a commemorative plaque was attached to the façade of the Dossin barracks as commemoration to this abomination. Since 1956, an annual ceremony is organised to commemorate the victims.

After the Centre for Administrative Service left in March 1975, the Dossin barracks fell into disrepair. The city considered demolishing the barracks but due to protests, the façade was put on the list of Listed Buildings. In 1977, ownership of the barracks was transferred from the state to the city of Mechelen, but only in 1980 it was decided to renovate the dilapidated building as an apartment complex. From now on, the barracks will be known as the ‘Habsburg Courtyard’, a reference to the Austrian rulers who built the complex and to the quietness within its walls.

Many people however thought it was inopportune to cast aside the history of the Dossin barracks as Sammellager. Therefore, the Vereniging van de Joodse Weggevoerden in België (VJWB) – Dochters en Zonen van de Deportatie (English: Association of Jewish Deportees in Belgium – Daughters and Sons of the Deportation) – and the Centraal Israëlitisch Consistorie van België (CICB) (English: Central Israeli Consistory of Belgium) pressured the city and the Flemish Community to keep a space in the barracks free for establishing a museum. Mr Natan Ramet, himself a survivor of the camps, was appointed chairperson. On 7 May 1995, the Joods Museum van Deportatie en Verzet (JMDV) (English: Jewish Museum of Deportation and Resistance) was ceremoniously inaugurated by HRH King Albert II. On 11 November 1995, the museum was opened for the public.

With 30,000 visitors per year, the JMDV quickly burst at the seams. Starting in 2001, the Flemish government developed plans for a new and larger museum. Because purchasing the entire Dossin barracks was impossible, they opted for a new construction according to a design by bOb Van Reeth, which contains the new permanent collection. A commemoration hall was furnished in the right wing of the old barracks building.

Flemish Prime Minister Kris Peeters and Bart Somers, the Mayor of Mechelen, opened the first part of the site, the Memorial, on 4 September 2012. This place of commemoration is situated in the front wing of the old Dossin barracks. The new museum on the other side was opened a few months later.

Kris Peeters, the Prime Minister of Flanders, opened the new Kazerne Dossin – Memorial, Museum & Documentation Centre on Holocaust and Human Rights in the presence of HRH King Albert II on 26 November 2012.

On 27 January 2020, the renovated Memorial opened its doors. This project would not have been possible without the extraordinary dedication of Mr Georges Ingber, whose memory we honour.